by Bruce Poinsette

(This is the second of two articles about artist-in-residence projects that RACC manages through the Percent for Public Art Program for the City of Portland.)

Spend a few minutes with Dr. Lisa Bates and Sharita Towne and the two women will have you questioning everything you’ve ever learned about the role of Black creativity in America. For the transdisciplinary artist and urban planner duo, the Black imagination is a tool for tangible change that they’re putting into action through their collaboration as the Black Life Experiential Research Group.

“The Black imagination isn’t about distraction,” says Towne. “We’re not using it to distract us from our reality. Our imagination is an underground railroad of meanings that is actually about derailing oppression. It’s in our imagination that we find a means of escape.”

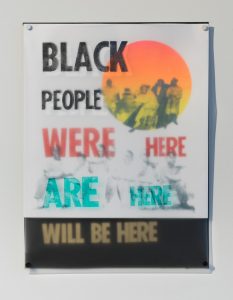

Officially described as an “interdisciplinary collaborative for inquiry and activism at the intersection of art, urban planning, and radical geography,” BLERG is a think tank that Towne and Bates began developing in the spring of 2017. With the support of the Regional Arts & Culture Council, BLERG is currently participating in an artist-in-residence program focused on the Humboldt neighborhood. Utilizing a variety of different artistic mediums, collaborators, and spaces, the project seeks to both build community and redefine the narrative around Black life in Portland. BLERG-related projects include a DIY newspaper called the “Black Life Sentinel,” collaborative events with local Black artists such as “This is a Black Spatial Imaginary,” ongoing oral history interviews with longtime residents of the Humboldt neighborhood and community, and collaborative learning experiences with students at Jefferson High School.

Towne and Bates are keenly aware that the term “think tank” evokes thoughts of a disconnected, sterilized approach. Bates specifically references the work of geographer Clive Woods when she notes that statistics and metrics like the “achievement gap” and measurements of “blight” have long been used to dehumanize Black communities. Yet, instead of running away from these analytical tools, she and Towne are working to repurpose them to serve Black Portlanders.

“He (Woods) asked the question, ‘Are we academic coroners? Is this just an autopsy over and over again?’ And then he turns and asks, ‘Isn’t it the same scalpel in the hands of a coroner that’s in the hands of a surgeon?,’” recalls Bates. “So how can we take these tools, instruments, and ways that we study and think and wield them with a different intention?

“How do you talk about struggle and oppression, but also talk about resilience and joy? How do we talk about how Black life continues in those conditions?”

Towne adds, “When Black people get together, be it across discipline or geographies, something shakes loose inside of us. New possibilities are born out of that. With a think tank, we’re not just interested in producing a dry, analytical report. We’re interested in producing an experience that is just as much ours as it is the people who end up collaborating with us to make it or the people who witness it and carry it forward in whatever work they might do that benefits Black life.”

In many ways, Towne and Bates’ vision for BLERG is informed by their past experiences in the areas of art, activism, and urban planning. Towne is transdisciplinary artist and educator who has spent significant time not just in Portland, but also Salem, Tacoma, and Sacramento. She has won a host of awards and produced a number of exhibitions throughout the country. Some of her recent local projects include the film workshop De-Gentrifying Portland and Our City in Stereo exhibition.

Bates, meanwhile, is professional urban planner and activist scholar. Like Towne, Bates has won awards for her work, which has included research stints not just in Portland, but post-Katrina New Orleans and Chicago. She has worked with a multitude of public agencies in Portland to develop equity plans and strategies, including previously serving on the board of directors for the Portland Housing Center.

Considering Bates and Towne’s mutual interest in exploring the roots of gentrification and studying Black space, it was only a matter of time before their paths crossed at the Portland City Club a little over a year prior to the creation of BLERG. After hitting it off, the two quickly developed a vision for a project. Among other things, one of their primary goals was to pivot the larger cultural narrative from Black Lives Matter to “Black Life Matters.” Specifically, they wanted to move away from just discussing the Black experience within the narrow prisms of racial oppression and state-sponsored violence, and instead focus on the entirety of what it means to be Black in Portland. For Bates and Towne, this meant celebrating Black life as an everyday experience and discussing historical Black places as a matter of geography.

Black Life Sentinel Issue One

One example of how this ideal manifests in their work is the “Black Life Sentinel.” The DIY newspaper, which is a collaboration with the Portland African American Leadership Forum, Northeast Coalition of Neighborhoods, and the Regional Arts & Culture Council, dedicates each issue to a specific subject of concern for Portland’s Black community. In the latest edition, the paper took on urban renewal. Specifically, the theme of the issue, as well as the title of an editorial by Bates and Towne, was “Is more urban renewal what North/Northeast Portland needs?” In addition to the editorial, the paper contains both current and historic pictures of North/Northeast Portland’s Black community, interviews and testimonials from Black residents, a copy of PAALF’s vision for valuing Black lives, a glossary of urban renewal-related terms, and even a copy of a press release and separate document from the City of Portland making the case for urban renewal.

With the assistance of PAALF, Towne and Bates distribute the papers through word of mouth. Bates says she was genuinely surprised to find out how many people were unaware that the City was considering expanding its urban renewal efforts. For her, it signaled a clear deficit in media coverage.

“Where is this being reported or talked about at?,” says Bates. “Is it not being framed or connected in away that makes sense to people? What happened here? Me, being in urban planning and being attuned to the urban renewal area here, I knew all about that. I just thought everybody knew about it because it’s a big deal and it’s this super historically significant site. And then I started talking to people and handing them papers, and they knew nothing about it.”

While she was surprised by the collective lack of knowledge about current urban renewal plans, Bates understands that the subject in general isn’t particularly accessible for most people. In addition to being considered “boring,” she says it is often depressing. Specifically, the constant research on exclusion, exploitation, displacement, and predatory lending weighs on her.

“It’s just all of these layers upon layers of ways that policy and planning and urban renewal have defined Black people and spaces with Black people in them as defective and unacceptable, then did things to those people to contain, remove, and acculturate them in some harsh way,” says Bates. “But it’s also extremely depressing and in some ways, a weird project for urban planning. Urban planning is inherently future looking. Urban planning is supposed to be about the 25 year plan.

“But what are the tools that would let us imagine a different future? All of the basic tools we have in planning just involve projecting forward from a baseline, assuming the baseline is okay. But if none of this is okay at all because we now understand where we came from, then what would be the thing? So you have to start getting into something that would be way more about the imagination and creative problem solving. It can’t just be learning how to do a population projection. It can’t just be the mainstream tools of real estate site analysis because that’s already got all the bad stuff baked into it.”

BLERG taps into the aforementioned creative problem solving in a variety of ways, including rethinking the very foundation of their approach. Perhaps the best example of this is their collaboration with Jefferson High School, which is part of a larger RACC-sponsored artist-in-residency in the Humboldt Neighborhood.

Inside Black Life Sentinel Issue One

For this portion of the project, Towne and Bates work with a Jefferson Senior Inquiry class that explores race and social justice. They visit the class anywhere from twice a month to twice a week. Unlike other courses that seek to engage students with local artists, they make a point of not going into the classroom with a set plan. Instead, they work with the teachers and participate in the activities the students are already doing. They also spend a lot of time simply listening and conversing with students to gauge their perspectives. Four months in, while they don’t have any set projects, a number of students have agreed to work with BLERG on oral history interviews with their family members. Others are currently working with Towne and Bates on gallery presentations set for this spring.

“It can sometimes feel meandering or time consuming for artists or people outside of the school,” says Towne. “At the same time, I think it’s important in a place like Jeff to not arrive with a formula that you want to plug them into as variables. I think Jeff is a high school that is often sensationalized in ways that those youth don’t need to be enduring in their high school experience and in the history of this neighborhood and community. We’re really interested in being there and seeing how we share inquiry and give each other life. That way, we can see what shakes loose out of the soundboarding of our shared stake in Black life in this place.”

Sarah Dougher, a local musician and Portland State University professor who helps teach Senior Inquiry at Jefferson, echoes Towne’s sentiments. She says she’s been particularly impressed with how Towne and Bates give students space and encouragement.

“One thing that is really meaningful for our students is when people come in and spend the time to get to know them and to develop relationships with them,” says Dougher. “Most of the time when an artist or writer comes in, students are put in a position to automatically like and trust what that person is doing. One thing that Sharita and Lisa do is understand that is actually not a given. Building relationships with students is part of what makes the learning happen. This means actually spending a lot of time in the classroom with us and doing what we’re doing.”

While the Jefferson collaboration doesn’t yet have a centralized project, one BLERG activity that Dougher says was especially impactful for her students was the “Curation Station” project. As part of this activity, Towne and Bates invited six artists of color representing a variety of different mediums to speak to students. The artists ranged from graphic designers to traditional museum curators. In the weeks following “Curation Station,” Jefferson students even chose one of the presenters to be the keynote speaker for their Black History Month Symposium.

Going forward, Dougher hopes the BLERG collaboration can serve as a model for expanding and developing similar projects at other schools. While she admits that between Jefferson, PSU, and BLERG, it requires an inordinate amount of planning and resources, she believes Towne and Bates’ deliberate, responsive approach is still very much worth the investment. Dougher believes this approach is especially important for introducing students to careers they may not otherwise engage with in a meaningful way.

“It sets up situations for students to interact with different kind of adults, particularly weird adults like artists,” says Dougher. “Most of the adults coming into a school setting are not like that.”

“For me, it’s not ‘Some young people of color saw a role model.’ That’s gross,” adds Bates. “It’s about someone seeing something that made them think about what they’re doing with their work in a different way.”

Inside Black Life Sentinel Issue One

In many ways, this undefined approach to working with Jefferson students is reflective of the BLERG project as a whole. By taking on a transdisciplinary approach that encompasses various artistic mediums, as well as community partners and spaces, Towne says it gives the project the advantage of being hard to contain.

“If I’m hitting something as hard and embedded as the white spatial imaginary of Portland and what it has done to generation after generation–if I’m hitting it with all these things in such a massive way, it creates these fissures that can be used in different ways to get to the meat of it and break it apart,” says Towne. “Whereas if it’s one particular angle, I find it’s very easy to get preoccupied with the medium or get preoccupied with the art. But when you use all these different things, it lifts us out of that. Then we can talk about the conceptual underpinning of what we’re dealing with rather than the cool video we saw.”

Going forward, Towne and Bates are working with a local library partner to host more programming that focuses on family and community history in the Humboldt neighborhood. As with all their other programming and activities, the ultimate goal is to create and expand opportunities for different members of Portland’s Black community to engage with each other. Despite the historic apprehension on the part of the City towards most Black organizing, Towne points out that the benefits of this engagement go far beyond the Black community.

“It’s out of that mutuality and solidarity of Black spaces that we see an emergence of the prescription to society’s problems,” says Towne. “As a Black Oregonian seeing and witnessing what that has meant to generation after generation of my family, the values we infuse into space and the way that we take care of people is something that really informs this project.

“When you look at North and Northeast Portland, you see the Black spatial imaginary also included Pacific Islanders. It included Vietnamese refugees. It included all of these people. And that’s what I think I’m interested in. I want people to realize that when we’re centering Blackness, it’s not to exclude anybody, ever. It’s just to acknowledge the way that our values have permeated into the landscape of this place and benefited a lot of people, even in moments of the most devastating segregatory policies of the 20th century.”

———————————————————–

¹The presentations will be held at PCC Paragon Gallery from Apr. 4-25.

²Derrais (d.a.) Carter, Roshani Thakore, Melanie Stevens, Black Life Experiential Research Group (Sharita Towne and Lisa K. Bates), Kayela J, and Ashley Stull Meyers.

³The Humboldt Neighborhood Artist-in-Residence project is a partnership between PCC Cascade, the City of Portland and RACC and made possible with funding from PCC Cascade and City Percent for Art funds from neighborhood street improvements. “It’s cool because it does allow for people to really get into the community and not just put up a tombstone that says, ‘They Black community was here,’” says committee member Donovan Smith. “It really allows them to dig in and find out what the community that’s here needs and reflect that back through different artistic avenues. I also like that they’re going through these different cycles so each artist has the chance to build off the work that came from the artist and residence before them.”

BRUCE POINSETTE is a versatile freelance writer, copy/content editor, editorialist, and speaker. Poinsette versatile work ranges from content creation to speechwriting. He has authored over 100 articles in five Portland area publications, including The Skanner, The Oregonian, Street Roots, Flossin’ Media, and We Out Here Magazine; in the collegiate curricula at Portland State University and University of Oregon. As a speaker, Poinsette has made presentations and participated in panels at various churches, K-12 schools, and universities. Poinsette has also conducted workshops on the journalistic interview. Find out more about Bruce and his work here.

BRUCE POINSETTE is a versatile freelance writer, copy/content editor, editorialist, and speaker. Poinsette versatile work ranges from content creation to speechwriting. He has authored over 100 articles in five Portland area publications, including The Skanner, The Oregonian, Street Roots, Flossin’ Media, and We Out Here Magazine; in the collegiate curricula at Portland State University and University of Oregon. As a speaker, Poinsette has made presentations and participated in panels at various churches, K-12 schools, and universities. Poinsette has also conducted workshops on the journalistic interview. Find out more about Bruce and his work here.